The Japanese tea ceremony itself is the highly developed ritual of offering tea to guests, an art form with important religious connotations.

The Japanese Tea Ceremony derives from Zen Buddhism, and it is the ritual instituted by Zen monks of successively drinking tea out of a bowl before the image of Bodhi Dharma, which laid the foundations of the tea ceremony. Bodhi Dharma was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century, traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to Chinese legend, he also began the physical training of the monks of the Shaolin Monastery that led to the creation of Shaolin Kung Fu.

In Japan, tea is not just a beverage. Indeed, tea masters devote their life to the tea ceremony. An art form itself, it goes through schools and periods, much like art would in the West.

The culture, or even religion, of tea is Teaism, also known as “the way of tea”, or chanoyu, which, in the words of Kakuzo Okakura is “a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence.”. Teaism had a profound effect on all aspects of Japanese life and its worldview. Indeed, one may say that the quintessential Japanese component is Teaism, and that the Japanese spirit bears its name. If bushido, the Code of the Samurai, could be called the Art of Death (though this is a gross generalization of this phenomenon), chanoyu is the Art of Life.

Japan has lived through three tea schools already: the boiled Cake-tea, the whipped Powder-tea and the steeped Leaf-tea, loosely relating to what Westerners would consider the Classic school, the Romantic school, and the Naturalistic school of tea, and derived from the Chinese Tang, Sung and Ming dynasties respectively. However, while the Mongol invasion of China in the 13th century caused the attempted re-nationalisation by the Ming dynasty in the 15th century, China’s internal troubles lead to China falling again under the rule of the Manchus in the 17th century, which would end with the last Emperor Puxi in the middle of the 20th century. The Ming dynasty saw the birth of the steeped tea, the school of tea the whole world practices unknowingly, since this is the current school of tea, and has been taken over with the import of tea by Western colonialists since their first trade with China. But the power struggles that occurred in China during these years proved to be the demise of a majority of the knowledge that had been amassed over the centuries. A Ming commentator would be at loss to recall the powdered tea of the Sung dynasty at all, which is still the school of tea practiced in the Japanese tea ceremony. Japan on the other hand, resisting the Mongol invasion of 1281, preserved all this culture, and has been able to thrive on it throughout the centuries, developing Teaism into the art of life.

Among the tea schools, the Leaf-tea is considered to be the least important school. In fact, many tea masters consider it to have lost the “zest for the meaning of life”, and more of a pleasant beverage. This is the reason why the tea school practiced during tea ceremonies is the whipped Powder-tea.

“It goes far beyond the art of preparing and enjoying a bowl of tea according to certain rules and encompasses all the activities and actions associated with it, all the equipment and utensils, and, last but not least, the surroundings of the tea room and garden. Different artistic genres such as architecture, garden design, ikebana, calligraphy and pottery are merged into a new whole.” Wolfgang Fehrer, The Japanese Teahouse

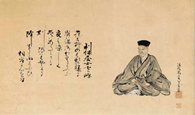

The founding father of the tea ceremony as an elevated high state formality would be Sen no Rikyû, living in the 16th century, considered as the greatest of all tea masters. He is the “individual who made the greatest impact upon this transformation into a refined aesthetic ceremony with profound philosophical and religious connotations”. Wolfgang Fehrer, The Japanese Teahouse

Its designated space, the teahouse, has a history of more than 1200 years. It had started as a mere section of the drawing room in residential houses, partitioned off by screens to offer a distinct space for receiving and entertaining guests with tea hospitality.

However, if the teahouses of China or the Middle East are public spaces, no different to Western cafés, they differ entirely from the Japanese teahouse, which is of a private nature and has acquired an almost sacred meaning over the centuries. Indeed, like geisha teahouses do not accept “first-time guests”, meaning that any new customer has to be introduced to the okaasan of the ochaya (teahouse in the entertainment districts where geisha entertain) by an already existing guest, you have to be invited to attend a tea ceremony.

You may wonder why the culture of tea would be of value in an architectural project. Indeed, in Japanese architectural tradition, the carpenter was usually also the designer of a building, until the teahouse came along, and for the first time, one figure fully impersonated the role of the architect, the planner and designer.

“Only with the advent of the teahouses did a paradigm shift emerge in this respect: Unlike the rest of the architectural work, the tea master who designed the building is not identical with the carpenter who built it. Japanese architecture thus only became familiar with the concept of authorship in architecture with the advent of the teahouse of the Momoyama period. Although there were individual buildings that were closely connected with the name of the client, clients never designed the building. The tea masters are thus among the first architects in Japan. It is symptomatic of this change that, from this point on, a connection between buildings and styles bearing the designer’s names – such as Rikyû-gonomi or Oribe-gonomi – appeared for the first time. Last but not least, the creative originality and individuality of the tea masters (sakui) is one of the most important driving forces in the development of the tea ceremony.” Wolfgang Fehrer, The Japanese Teahouse

At this point I would also like to mention that, though this is not a detailed study of the Japanese teahouse, it is a very varied one and includes aspects from multiple areas of the Japanese world. This is mainly because without all this information, we, as Westerners, will not be able to begin to understand the meaning of the different factors in question. Indeed, the teahouse itself is a fitting example of this phenomenon: in the West, we simply do not have an equivalent, and therefore are at loss when confronted with its existence. The same goes for geisha, which the West struggles to identify as a figure ranging from prostitutes to ladies in waiting, or yakuza, foolishly considered to be the mere “Japanese criminals” in the West. This is simply because it’s a whole different world, a different thinking, a different mindset, and everything from the perception of what is beautiful to the chart of morals is judged accordingly to a completely distinct sense of logic. I would therefore like to clarify that, though we try our best to understand and admire Japanese culture, we will not succeed at it, simply because our own values are too intimately ingrained in our minds. However, this doesn’t mean that one cannot learn from it and be inspired by its marvels either, something we shall imminently practice with great care.

“The tea room sukiya wants to be nothing more than a simple cottage – a straw hut, as we call it. The original characters for sukiya mean „place of fantasy“. Later, the various tea masters used various other signs that corresponded to their concept of the tea room, and sukiya can mean place of emptiness or place of asymmetry. It is a place of fantasy insofar as it is built to be a temporary home of poetic emotion. It is a place of emptiness inasmuch as it is without adornment, except for the few things needed to satisfy an instantaneous aesthetic need. It is a place of the asymmetrical in that it is dedicated to the worship of the imperfect, leaving with intent something imperfect in order to be completed in the play of imagination. […] The ordinary Japanese interior of the present day, on account of the extreme simplicity and chasteness of its scheme of decoration, appears to foreigners almost barren.” The Book of Tea, Kakuzo Okakura, 1906

Though unimpressive in its appearance, the teahouse is considered to be the gem of Japanese architecture. Not because of its small size, but simply because it best represents all Japanese values, deeply ingrained in religion. Unimpressive in appearance, its construction calls for the mastery of all artisans involved.

“the materials used in its construction are intended to give the suggestion of refined poverty. Yet we must remember that all this is the result of profound artistic forethought, and that the details have been worked out with care perhaps even greater than the expended on the building of the richest palaces and temples. A good tea-room is more costly than an ordinary mansion, for the selection of its materials, as well as its workmanship, requires immense care and precision.” Kakuzo Okakura, The Book of Te

The style of the tea-room, outstanding even among the architecture of Japan, resulted from emulation of the Zen monastery, since the latter is only a dwelling place for the monks, rather than a place of worship and pilgrimage.

The strong religious connotations in the aspect and building of the teahouse make it a unique phenomenon only comparable to the tea ceremony itself. Indeed, it is one of the rare buildings of which the architecture dictates a use, unlike the usual Japanese room, which is open to a wide variety of uses through the employment of removable shoji screens and sparse, light furniture, like the futon beds.

However, the tea ceremony can be carried out in various establishments, or even outdoors. Geisha for example are all trained in the tea ceremony, and perform it on multiple occasions, sometimes even for hundreds of people at events like the Miyako Odori, the spring dances of the Gion Kobu geisha district in Kyoto. The magnificent large reception rooms used for tea ceremonies in the shogun palaces and residential homes of samurai are known as shoinrooms, the spectral opposite to the simple grass-roofed sôanhut modeled on the hermit’s mountain hermitage.

In this case we’ll be exclusively interested in the sôan teahouse, which has the richest history and has emerged as the most suitable form of teahouse. It was first built by the tea master Jôô in the 16th century, and has been perfected by his student Sen no Rikyû, recognized as the greatest tea master of all time.

“The classic tea room, first built by tea master Jôô in the 16th century and brought to perfection by his student Sen no Rikyû, is a room the size of 4 1/2 tatami mats with the floor area of around 8 m² usually it does not offer space for more than five people.” Wolfgang Fehrer, The Japanese Teahouse

In order to understand roughly how a tea ceremony is conducted, here a useful guide from worldteanews.com:

“[On the day of the tea ceremony, the host rises very early in the morning to start preparations.]

During traditional Japanese tea ceremonies, the teahouse, including the garden outside, is thoroughly cleaned and sanitized. The utensils have been carefully selected by the host, and meals are prepared in advance.

There are certain circumstances and elements that affect the order of each step. The season, time of day, and venue can all modify the step, but the same general steps are typically followed in most cases:

Step 1: The Preparation for the Tea Ceremony

The host will generally prepare weeks in advance for the ceremony. Formal invitations will also be sent out, and the host will prepare their mind, body, and soul for the ceremony. Additionally, the host will prepare the utensils and clean the tearoom, as well as the outside of the tearoom, which may have a garden.

Step 2: The Guest’s Preparation for the Ritual

Before entering the tearoom, guests should prepare themselves by leaving worldly things behind and purifying their souls. Guests should also wash their hands before entering the tearoom to remove the “dirt” from the outside world.

Once the host gives the signal to enter, the guest should bow to the host. This gesture shows respect and appreciation for the host’s efforts.

Step 3: Cleansing of the Tools

The host will bring in the tools to make the matcha and clean them in front of the guests before the actual making of the tea begins. [This used to be done to show rival samurai guests that the utensils were not poisoned.] A silk cloth (fukusa), representing the host’s spirit, is taken from their kimono sash. It’s symbolically inspected, folded and unfolded, before being used to handle the hot iron pot. [In Kyoto there are still merchants who exclusively trade with fukusa.]

The host will also exhibit the importance of the tools and show a graceful posture. It’s considered disrespectful to talk or make any movements during the cleansing of the tools.

Step 4: Preparing the Matcha

Once the tools are cleaned and displayed in front of the guests, the preparation of the matcha begins. The host will generally add three scoops of matcha in the tea bowl for each guest. Next, the hot water is added and whisked until it forms a thin paste, and more hot water is added afterward.

Step 5: Serving the Matcha

Once the matcha is made, the tea bowl is exchanged with the main guest (shokyaku), who generally admires and rotates the bowl by 180° before taking a sip. This is so as to avoid drinking from the decorative front of the bowl, [as it would be impolite to not permit the tea master or other guests to view this side of the bowl. At the same instance, the tea was prepared by the tea master with the decorative front of the bowl facing towards the guests, which is why the guest turned it in the first place]. The main guest should wipe the rim of the bowl and present it to the next guest, who repeats the same procedures until the bowl is passed to the last guest. This person, in turn, gives it back to the host. [Pretty wagashi sweets, sometimes made from azuki bean paste, are served to complement the bitterness of the tea.]

Step 6: Completion of the Ceremony

After all the guests have received a drink of matcha, the host will clean the utensils. As a sign of respect and admiration for the host, the guests will use a cloth and carefully examine the tools used to make sure they’re properly cleaned. Once this has been completed, the host will gather the utensils as the guests make a final bow and exit the tearoom.

It’s also important to note, the host may prepare either thin matcha (usucha) or a thicker brew (koicha) for a tea ceremony.”

I would like to note that neither the cleanliness of the teahouse, the different seating orders, the appearance of the guests or the comportment inside the teahouse are noted in this description.