In the West, boundaries between the spaces of different functions and natures are clearly delimited. In Japan, the border itself is seen in less absolute terms. Indeed, the teahouse shows that perfectly with the border between the teahouse and the tea garden being a very permeable one. The border itself is more of an indication rather than a physical distinction, keeping the contact and flow. One could compare it to the debate of the painters in the 19th century between Ingrès and Delacroix: is it the line that delimits or the adjacence of colour?

The idea of the border kekkai (literally “a marking that separates spaces”) takes up this idea when it simultaneously acts as a separating element and as a link between the persons and spaces between whom it is erected, thus representing this specific dialectical relationship. It originated from the fences surrounding shrines of the Shinto sanctuaries in several layers. As a rule, they allowed at least a glimpse of the most holy, the inner shrine, without revealing a view of the whole. Indeed, the early Shinto shrines were only marked by a sacred straw rope called shimenawa, enclosing a sacred area. Here we once again find the concept of oku.

“Enclosure is the result of surrounding an object or a space so as to “inform” the contained space or object. An enclosure can be thought of as a wrapping and is quite a distinctive aspect of Japanese space.” Chin-Yu Chang, Japan Architect

Interiority and exteriority

The Japanese teahouse is the quintessential Japanese building, in that it’s the simplest, purest form of Japanese building principles. On the other hand, it is also unique in Japanese architecture, because it can only be used for the tea ceremony, and all living dwellings therefore need further elements.

However, Japanese building aesthetics are very clear and defined. Interiority and exteriority are not defined by walls like in Western architecture, but by the raised floor, once again emphasising the importance of the Japanese connection to nature. Interiority is only a temporary dwelling in a human environment, made to fade amidst the surrounding nature. To quote Sen no Rikyû once more:

“Enjoying a wonderful apartment and delicious food are ordinary, worldly pleasures. A house through whose roof it doesn’t rain is enough for us.”

The importance of floorspace for Japanese culture cannot be overestimated. Since Japanese houses are lifted from the ground, there was no need for furniture that would elevate its inhabitants from the damp or cold floor. The raised floor is enough to make that distinction, and, from a structural point of view, provides ventilation, which is important in the hot, humid climates of Japan:

“When you build a house, you should remember summer. In the winter you can live anywhere, but there is nothing worse than a house that proves unsuitable for the hot season.” Hermit Yoshida Kenko

Indeed, this is why, even if you have passed a door, you will only enter the house when climbing up. The Japanese invitation to enter a house is therefore not “please step inside”, but “agatte kudasai”, meaning “please step up”. The Japanese architectural theorist Yoshinobu Ashihara goes so far as to classify Japanese building as “architecture on the floor” in his book The Hidden Order – Tokyo through the Twentieth Century. And so in Japan it is rather the floor, and not the wall, that separates the interior from the exterior. This is also seen in the element of tatami as a dictate of floor surface.

“Only a few supports, the surface of the raised floor, and the protruding roof mark the interior of the house, which together with a transitory space of the veranda forms a continuum with the exterior space.” Wolfgang Fehrer, The Japanese Teahouse

Thus, even without the religious conceptions of the Japanese teahouse, our structure would be considered a room in Japan.

At this point, it is interesting to note the characteristic opening of the teahouse, the nijiriguchi.

“The teahouse in entered via a 60-centimeter high “crawl door”, originally designed to make samurai leave their swords (and egos) behind and to come in with a pure and humble mind. Inside all participants of the tea ceremony are considered equal, regardless of rank.” David and Michiko Young, The Art of Japanese Architecture

This is once again interesting in relation to the nearby situation to Aigues-Vertes. Above all else, our ROOM is a symbiosis, and this includes one between the inhabitants of Aigues-Vertes and the outside world. The teahouse as a house of peace is thus an extremely strong metaphor.

“[the] samurai will leave his sword on the rack beneath the eaves, the tea-room being pre-eminently the house of peace.“ Kakuzo Okakura, The Book of Tea

The term nijiriguchi derives from a slang term used by carpenter, according to Arthur Sadler. It used to be a door through which the guests could enter the tearoom in an upright posture, however, since Rikyû, the size of 79 x 72 cm became the first classical entrance dimensions. The standard size would be 66 x 66 cm. They can be cut out of an old door, or made from posts and boards.

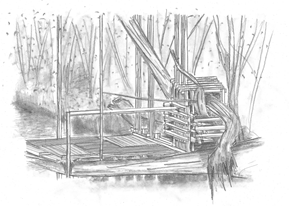

In our case, since we do not have walls, we simply elongated present axis in order to create a square of the right dimensions, through which, if one follows the natural roji of the fallen tree, one is forced to enter.

According to legend, Rikyû was influenced by the hatches of river ships he saw in northern Osaka. Chadô Shiso Densho reported:

“Finding it to be tasteful and interesting that one must crawl into and out of the boats at the dock at Hirakata in Osaka, Rikyû began to use such a passageway in a small tea room.”.

The way in which the nijiriguchi forces the visitors to enter a tea room did not always arouse undivided enthusiasm. Dazai Shundai, a samurai from Shimano province and critic of the tea ceremony, commented:

“The entrance-way for guests is like one suitable for dogs. Obliged to crawl in on the belly, one has a suffocating feeling. In the winter it is unbearable.”.

The low entrance forces every visitor to enter the tea room in a humble posture. At the same time, it is a sign that one crosses a threshold and enters another world. As in the Nô or Kabuki theatre, where visitors have to squeeze the way through the so-called “mousehole” nezumi-kido after they have paid admission, or the musicians only enter the stage through a narrow gate, there is also a separation between the profane and the sacred world in the tea room. In this context it is interesting to note the idea of Japanese Amida Buddhism, in which one can enter Paradise only through a small opening.