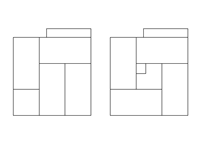

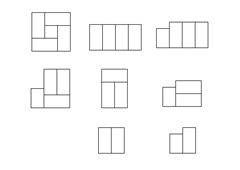

The “classic” floorplan of 4½ tatami is called the yojôhan. Tearooms larger than that are called hiroma, the “wide room”, with a size as big as 15 tatami, though that is rare. Usually, they do not exceed 8 tatami. Tearooms smaller than the yojôhan are called koma, “narrow rooms”. They are by far the most common, and can be divided into 7 different types:

–naga yojô, the “long 4-mat room”, in which the four mats are placed next to each other, the long sides adjacent;

–hira sanjô-daime, the “wide 3¾-mat room”, much like the naga yojô, with the tatami on the end being replaced by a ¾ one;

–fuka sanjô-daime, the “deep 3¾-mat room”, in which two full tatami, aligned on their long side, meet at the joint between the ¾ tatami and the remaining full one;

–sanjô, the “3-mat room”, which is the fuka sanjô-daime without the daime (the ¾ tatami);

–nijô-daime, the “2¾-mat room”, where the daime meets the two full tatami, adjacent on their long sides, on their short side;

–nijô, the “2-mat room”, essentially the nijô-daime without the daime;

–ichijô-daime, the “1¾-mat room”, corresponding to the nijô, substituting one of the full tatami with a daime.

Although the floor plans with two and 4½ matts are often square, the individual elements in the tea house never obey a symmetrical order, and the same design pattern is never repeated. The striving for asymmetry manifests itself in the constant effort not to repeat any form or colour in the tea room -tension is always sought between large and small, round and angular, light and heavy.

We ourselves used the yojôhan.

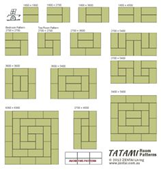

The tatami themselves are considered to define the smallest possible living space. Their size was unified over the centuries, even though it still differs depending on the region. The ratio of length to width always remains 2:1 however. In Kyoto, they are usually 191 x 95.5 cm, called kyô-ma-tatami, characteristically of the Kansai region, also including Kobe and Osaka. They are slightly larger than the ain-no-ma, “interspace” tatami found in Nagoya, and even larger than the inakam-datami from the Kantô plain around Tokyo. All can be seen used in tearooms throughout the centuries, though the Kyoto style has been able to establish itself as the reference size.

They are made of the thick toko bottom layer, which is made of rice-straw, pressed to a thickness of about 4 cm. The actual straw mat is called omote. The edges of the mats on the long sides are finished by fabric borders, traditionally black, but a marvellous variety exists, depending on the location and position of the owner. The imperial tatami can be incredibly colourful. In the teahouse however, it will be rare to see anything but black, the famous Edo-blue or a subdued grey. Often, they last lifetimes, since only the mat on its surface needs to be replaced every few years. The artisans making tatami are still working traditionally by hand, and are able to renew the omote of a standard tearoom in one afternoon.

We did not use tatami for obvious reasons, since we are not interested in copying, and because the materials are hardly available. However, we used the wood lattes of the floor to emulate the floorplan and respect the kyô-ma-tatami size.

Floor plans can also be classified by the position of the rô, the sunken stove. The rô is only sunken in the actual floor in winter, during the summer, a portable stove will be used on a protective layer directly on the tatami. The different positions differ according to its relation with the seat of the host. The four basic types are the classic yojôhan, and the daime, which, along with the mirroring of the entire floor plan, can be in the “right-handed” or “left-handed” position.